科学文献

Why are so many young people getting cancer now ? What do the data on cancer rates among young people tell us? Mysteries and clues may lie in information collected generations ago.

As the prevalence of many cancers among young people continues to rise, scientists and clinicians are looking to explain this phenomenon. Statistics from countries around the world show that the prevalence of more than a dozen cancers, including colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, stomach cancer, breast cancer and prostate cancer, is increasing in adults under 50 or even younger.

The reasons for this growing trend are still not entirely clear. Some studies have shown that it is related to factors such as rising obesity rates among young people and early cancer screening (early cancer screening at age 45), but it still cannot explain this global phenomenon (screening rates in underdeveloped countries are not early).

Researchers have begun to explore possible causes, including changes in the gut microbiome and tumor genomic features, as well as exposure groups. It is known that some people's genetic factors, changes in the gut microbiome, and long-term changes in living environment and lifestyle (exposomes), such as unhealthy eating habits and processed foods, and unhealthy prenatal factors in women, have all been included as possible factors.

International cooperation agencies hope to find out the main reasons for the increase in cancer among young people through detailed analysis of cancer data over the past few decades. Early cancer screening and preventive treatment, including vaccination, for young people can be carried out to avoid unnecessary premature deaths from cancer. Pay attention to the report details.

"If the evidence is strong, our study would at least point to one factor," said Sonia Kupfer, a gastroenterologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois. "But it appears to be a combination of different factors that cause cancer."

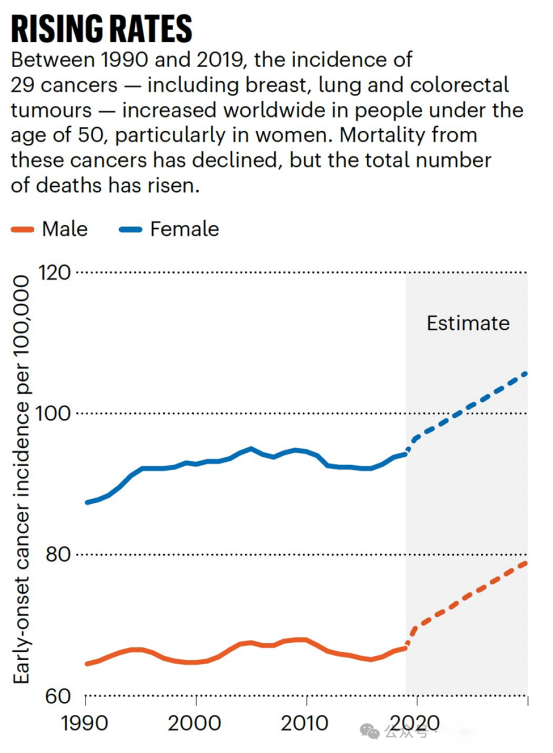

Early-onset cancer usually refers to cancer that occurs in people under the age of 50. Medical research data in recent years show that the incidence of various types of early-onset cancer is on the rise worldwide. A study published in BMJ Oncology showed that in 2019, the number of early-onset cancer cases worldwide exceeded 3.26 million, with an incidence rate that increased by 79.1% and a mortality rate that increased by 27.7% compared to 1990.

By type, the largest increases were seen in cancers of the digestive system, such as colorectal, pancreatic and stomach cancers. Globally, colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers and tends to get the most attention. But rates of breast and prostate cancers are also rising.

Some researchers believe that rising obesity rates and a diet high in processed foods may be to blame for the rise in early-onset cancers, but Daniel Huang, a hepatologist at the National University of Singapore, believes these factors are not enough to fully explain the trend of younger cancers.

Other researchers are looking for genetic clues. Shuji Ogino, a pathologist at Harvard Medical School, and his colleagues have found possible features of aggressive tumors in early-onset cancers. For example, aggressive tumors are sometimes particularly good at suppressing the body's immune response to cancer. But researchers have not yet found a clear boundary between early-onset cancers and late-onset cancers.

Microbes are also thought to be involved in early-onset cancer. Disruption of the microbiome, caused by dietary changes or antibiotics, has been linked to inflammation and an increased risk of multiple diseases. But current findings are still preliminary, and collecting long-term data faces difficulties. "The factors that influence the microbiome are so wide-ranging," said Christopher Lieu, an oncologist at the University of Colorado Cancer Center. "You ask people to recall what they ate as a child, and I can barely remember what I had for breakfast."

Scaling up the study could help. Cathy Eng, an oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in the United States, is studying the correlation between microbiome composition and cancer at a young age, and she plans to combine her data with those of collaborators in Africa, Europe and South America. Kimmie Ng, founding director of the Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in the United States, commented that the number of early-onset cancer cases in any one center is still small, and this international collaboration is very important to increase statistical analysis power.

Another approach is to look closely at differences between countries. Japan and South Korea, for example, are neighbors with similar economic development. But early-onset colorectal cancer is increasing faster in South Korea than in Japan, says Tomotaka Ugai, a cancer epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School. Ugai and his collaborators hope to determine why.

But data is scarce in some countries. Boitumelo Ramasodi, South African regional director of the Global Colon Cancer Association, a US nonprofit , said cancer data in South Africa is collected from only 16% of the population with health insurance. Families rarely record people who die from cancer. In this country, cancer is considered a white person's disease.

The researchers say they need to look back in history to find possible reasons from large-scale longitudinal studies. Studies have shown that cancer can appear many years after exposure to carcinogens, such as asbestos or cigarette smoke. The researchers need to collect 40-60 years of data from thousands of people.

Barbara Cohn, an epidemiologist at the Public Health Institute in Oakland, California , has compiled a rare repository of data and blood samples collected during pregnancy from about 20,000 women since 1959. Since then, researchers have followed many of the original participants and their children. Cohn and Caitlin Murphy, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, have tried to comb through the data and found a possible link between early colorectal cancer and prenatal exposure to a specific synthetic form of progesterone. But the study must be repeated in other cohorts to confirm the association.

Finding cohort studies that span the prenatal period into adulthood is a challenge. The ideal study would recruit thousands of pregnant women in several countries, collect data and samples of blood, saliva and urine, and then follow them for decades, Ogino said.

“Right now, it’s important that doctors share data on early-onset cancers and follow up with patients after they complete treatment to understand how best to treat them,” said Irit Ben-Aharon, an oncologist at Israel’s Rambam Health Care Campus. Some cancer drugs can cause cardiovascular problems or even lead to secondary cancers years after treatment, and these risks become more worrisome in younger people.

Young people may become pregnant during diagnosis or be more concerned about the impact of cancer drugs on their fertility. They are still far from retirement and are more concerned about whether cancer treatment will cause long-term cognitive damage and hinder their ability to work.

Surgeon George Barreto, whose friends and family had developed early-onset cancer, was determined to find out why. He wanted to study the impact of prenatal stress, such as exposure to alcohol, cigarette smoke or poor nutrition, on early-onset cancer risk. He contacted scientists around the world, but no biobank project contained the data and samples he needed. He said it was understandable if the data he and others needed were not available now. But if there was still no data 20 years later, it would be a failure.